Adresse

304 North Cardinal

St. Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Heures de travail

Du lundi au vendredi : de 7h00 à 19h00

Le week-end : 10H00 - 17H00

Adresse

304 North Cardinal

St. Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Heures de travail

Du lundi au vendredi : de 7h00 à 19h00

Le week-end : 10H00 - 17H00

Il est 2 heures du matin, un mardi. Votre téléphone sonne sur la table de nuit et l'identification de l'appelant est le responsable de l'équipe de nuit de l'usine. Votre cœur se serre. Ce ne sont jamais de bonnes nouvelles. Un orage a traversé la région il y a une heure, mais il était à des kilomètres de là - aucun impact direct, pas même un scintillement dans les lumières de votre maison. Mais la voix du superviseur est frénétique. “La ligne 3 est en panne. L'automate principal, deux variateurs de vitesse et la moitié des cartes d'E/S sont grillés. Nous sommes complètement à sec”.”

Je suis ingénieur d'application principal depuis plus de 15 ans et je ne saurais dire combien de fois j'ai entendu une variante de cette histoire. Le coupable n'est pas l'orage lui-même, mais le tueur invisible qu'il envoie le long des lignes électriques : une surtension transitoire, ou ce que nous appelons communément une surtension. Il s'agit d'une pointe électrique à haute énergie et de courte durée qui peut paralyser ou détruire des appareils électroniques sensibles en l'espace d'une microseconde. Le coût n'est pas seulement de quelques milliers de dollars pour un nouvel automate ; il s'agit de dizaines ou de centaines de milliers de dollars en perte de production, en délais non respectés et en frais de réparation d'urgence.

La plupart des installations se croient protégées parce qu'elles disposent d'un système de paratonnerre externe. Mais ce système ne protège que la structure du bâtiment contre les coups de foudre directs. Il ne fait rien pour arrêter les surtensions électriques massives qui sont conduites et induites dans vos lignes d'alimentation, de données et de communication.

C'est là que les dispositifs de protection contre les surtensions (DPS) entrent en jeu. Mais la question que j'entends le plus souvent est la suivante : “De quels dispositifs ai-je besoin ? Et où ? Dois-je installer des parafoudres sur chaque panneau ?” La réponse n'est pas simplement “oui” ou “non”. La bonne réponse est une réponse stratégique, fondée sur la compréhension des différents types de DOCUP et des technologies qu'ils contiennent. Ce guide vous aidera à comprendre le pourquoi, le quoi et le où de la protection contre les surtensions, depuis le branchement jusqu'à l'équipement le plus sensible de votre étage, en se concentrant sur une approche approfondie de la protection contre les surtensions. Comparaison des matériaux entre les DOCUP de type 1, de type 2 et de type 3.

Avant de nous pencher sur les différents types de disjoncteurs, clarifions ce que fait réellement un disjoncteur. Considérez votre système électrique comme un système de plomberie avec une pression d'eau (tension) normale et constante. Une surtension est comparable à un coup de bélier soudain et massif - un pic de pression qui peut faire éclater les canalisations et endommager les appareils.

Un DOCUP agit comme une soupape de décompression. Dans des conditions de tension normales, il reste là, sans rien faire, et présente une impédance élevée. Mais lorsqu'il détecte un pic de tension supérieur à un certain seuil (sa tension de serrage), il crée instantanément un chemin à très faible impédance pour dévier cet excès d'énergie en toute sécurité vers la terre. Dès que la tension revient à la normale, la “valve” se referme. Tout cela se passe en quelques nanosecondes.

Les surtensions proviennent de deux sources principales :

Comme ces menaces proviennent à la fois de l'extérieur et de l'intérieur, un seul parasurtenseur ne suffit pas. La stratégie la plus efficace est une approche coordonnée et stratifiée connue sous le nom de “défense en profondeur”. Imaginez un système de filtration de l'eau : une grille grossière à l'entrée retient les grosses pierres, un filtre plus fin en aval retient les sédiments et un dernier filtre au carbone au robinet garantit la pureté de l'eau. Les DOCUP fonctionnent de la même manière en cascade : Pas seulement une solution unique

Un système de protection contre les surtensions en couches ou en cascade.

L'industrie, guidée par des normes telles que UL 1449 et la série IEC 62305, a classé les SPD en “types” en fonction de l'endroit où ils sont installés et du type de surtension qu'ils sont conçus pour gérer. Comprendre cette classification Type 1 vs Type 2 vs Type 3 SPD la hiérarchie est le fondement d'un plan de protection solide.

Un disjoncteur de type 1 est la première ligne de défense de votre système. Il s'agit d'un gardien robuste installé au niveau du branchement, à l'endroit où l'électricité entre dans votre bâtiment. Il peut être installé soit du côté “ligne” (avant le disjoncteur principal), soit du côté “charge” (après le disjoncteur principal), mais sa tâche principale est de s'attaquer aux surtensions externes les plus puissantes.

Un disjoncteur de type 2 est le type le plus courant, protégeant les sous-panneaux et les tableaux de distribution dans l'ensemble d'une installation. Il est conçu pour être installé du côté de la charge d'un dispositif de protection contre les surintensités (comme un disjoncteur).

Un disjoncteur de type 3 est le dernier niveau de protection, situé juste à côté de l'équipement qu'il protège. Ce sont les dispositifs que l'on trouve dans les barrettes d'alimentation protégées contre les surtensions, les adaptateurs enfichables ou, parfois, directement intégrés dans les appareils électroniques sensibles.

| Fonctionnalité | DOCUP de type 1 | DOCUP de type 2 | DOCUP de type 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lieu d'installation | Entrée de service (côté ligne ou côté charge) | Panneaux de distribution/de dérivation (côté charge) | Point d'utilisation / Prise murale |

| Cible principale | Surtensions externes à haute énergie (foudre) | Surtensions résiduelles externes et internes | Surtensions résiduelles de faible intensité et surtensions locales |

| Forme d'onde de test | 10/350 µs (Iimp) | 8/20 µs (In) | 8/20 µs (In) et onde combinée |

| Capacité de surtension | Très élevé (par exemple, 25-100 kA Iimp) | Moyenne à élevée (par exemple, 20-60 kA In) | Faible (par exemple, 3-10 kA In) |

| Technologie principale | Entrefer, tube de décharge des gaz (GDT) | Varistance à oxyde métallique (MOV) | MOV, diode TVS |

| Protection Focus | Détournement d'énergie massive | Réduction des surtensions fréquentes | Tension de serrage la plus faible (VPR/Up) |

Qu'y a-t-il donc à l'intérieur de ces dispositifs qui leur permette de réaliser ces prouesses d'ingénierie électrique à grande vitesse ? Le “type” de DOC définit son application, mais c'est la technologie des composants à l'intérieur qui fait le vrai travail. Le choix du matériau détermine les performances, la durée de vie et le coût du dispositif. Vous trouverez quatre composants principaux, souvent utilisés dans des combinaisons hybrides.

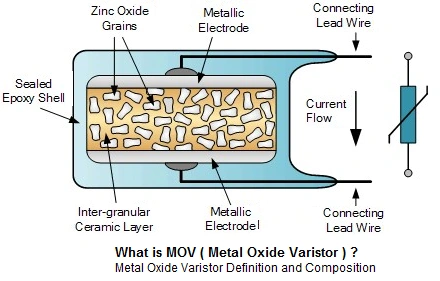

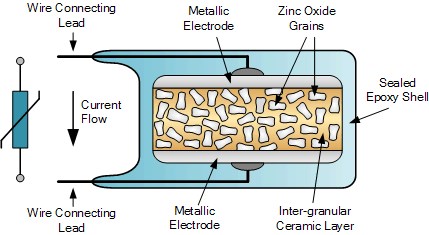

Le MOV est le cheval de bataille incontesté du monde de la protection contre les surtensions, présent dans la grande majorité des SPD de type 2 et de type 3. Il s'agit d'un dispositif semi-conducteur en céramique (principalement de l'oxyde de zinc avec d'autres oxydes métalliques) qui agit comme un interrupteur sensible à la tension. À des tensions normales, les limites des grains créent une résistance élevée. Lorsque la tension monte en flèche, ces limites se brisent en quelques nanosecondes et la résistance tombe à près de zéro, renvoyant le courant de surtension à la terre.

Un GDT est un dispositif simple mais puissant composé de deux ou plusieurs électrodes scellées dans un petit tube en céramique rempli d'un gaz inerte. Lorsque la tension entre les électrodes dépasse la tension de claquage du gaz, un arc se forme, créant un chemin à très faible résistance (un court-circuit virtuel).

L'éclateur est le premier dispositif de protection contre les surtensions par “force brute”. Dans sa forme la plus simple, il s'agit de deux conducteurs séparés par un petit espace d'air. Lorsqu'une tension très élevée se produit (comme celle de la foudre), un arc électrique saute l'espace, détournant le courant. Les “éclateurs déclenchés” modernes sont des versions plus perfectionnées qui utilisent une troisième électrode ou un circuit électronique pour se déclencher de manière plus fiable et à des tensions plus faibles et mieux contrôlées.

Les diodes TVS sont des dispositifs à semi-conducteurs, comme les diodes Zener super rapides, conçus spécifiquement pour la protection contre les surtensions. Ce sont les instruments de précision du monde des SPD, qui fixent la tension avec une précision chirurgicale.

| Technologie | Temps de réponse | Capacité de courant de choc | Durée de vie / Dégradation | Précision de serrage | Coût relatif | Application primaire |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOV | Rapide (~25 ns) | Moyen à élevé | Se dégrade avec chaque surtension | Bon | $$ | Type 2, Type 3, Hybride T1 |

| GDT | Moyenne (~100 ns) | Très élevé | Longue ; robuste | Juste | $$$ | Type 1, lignes de données/télécoms |

| Décalage de l'étincelle | Lent (>100 ns) | Extrêmement élevé | Très longue | Pauvre | $$$$ | Type 1 (usage intensif) |

| Diode TVS | Très rapide (<1 ns) | Faible | Longue (si elle n'est pas trop sollicitée) | Excellent | $ | Type 3, protection au niveau du conseil d'administration |

Principaux enseignements : Souvent, le DOCUP parfait n'est pas le fruit d'une technologie unique, mais d'un ensemble de technologies. conception hybride qui exploite les points forts de chacun. Une combinaison courante et très efficace dans un SPD de type 1 ou de type 2 à haute performance est un GDT ou un Spark Gap pour la gestion de l'énergie massive, associé à un MOV pour gérer le temps de réponse et la tension de serrage, assurant à la fois une protection par la force brute et un serrage rapide et précis.

Passons maintenant à la partie la plus importante : comment appliquer tout cela à votre installation ? Une bonne conception suit un processus clair et logique.

La norme IEC 62305 introduit le concept de zones de protection contre la foudre (LPZ). Imaginez votre bâtiment comme une série de boîtes emboîtées, chaque couche offrant une protection accrue. Votre objectif est d'installer un dispositif de protection contre la foudre à la limite de chaque transition de zone afin de réduire progressivement l'énergie de surtension.

Le concept de zone de protection contre la foudre (LPZ), montrant l'emplacement du SPD aux limites de la zone.

Utilisez cet arbre simple pour guider votre processus de sélection.

J'ai vu des systèmes SPD de plusieurs milliers de dollars rendus inutiles par une installation bâclée. La physique ne pardonne pas. Suivez ces règles à la lettre.

1. Puis-je simplement installer un SPD de type 3 (comme une multiprise) et ne pas utiliser les plus gros SPD ?

Non. Il s'agit d'une erreur courante et coûteuse. Un appareil de type 3 n'est conçu que pour gérer de petites surtensions résiduelles. Une surtension importante provenant de la compagnie d'électricité ou d'un coup de foudre à proximité le détruira, ainsi que probablement l'équipement qui y est connecté. Il a besoin des dispositifs de type 1 et de type 2 situés en amont pour réduire la surtension à un niveau gérable.

2. Comment savoir si mon parasurtenseur doit être remplacé ?

La plupart des disjoncteurs modernes montés sur panneau (types 1 et 2) sont dotés d'un voyant d'état ou d'un drapeau mécanique. Le vert signifie généralement que l'appareil fonctionne ; le rouge, l'arrêt ou une couleur différente signifie que la protection a été compromise et que l'appareil doit être remplacé. Certains systèmes avancés disposent également de contacts de surveillance à distance qui peuvent être reliés à votre système de gestion des bâtiments.

3. Quelle est la différence entre un parasurtenseur et un disjoncteur ?

Un disjoncteur protège contre surintensitéIl s'agit d'une condition dans laquelle le système tire trop de courant pendant une période prolongée (par exemple, un court-circuit ou un moteur surchargé). Il s'agit d'un dispositif thermo-magnétique à action lente. Un SPD protège contre surtension-Une pointe de tension extrêmement rapide et de courte durée. Ils remplissent deux fonctions de protection complètement différentes mais tout aussi importantes l'une que l'autre.

4. Un parasurtenseur protège-t-il mon équipement d'un coup de foudre direct ?

Aucun dispositif ne peut offrir une protection 100% contre un coup direct sur la structure elle-même. Un système de protection contre la foudre (SPF) correctement installé gère le coup direct. Un SPD de type 1 est conçu pour gérer l'immense courant qui arrive à la structure. sur les lignes électriques à partir de cette grève. Il s'agit de deux parties d'un système complet.

5. Une valeur de kA plus élevée est-elle toujours préférable ?

Jusqu'à un certain point. Un indice kA plus élevé (pour Iimp ou In) signifie que l'appareil peut supporter plus d'énergie de surtension ou plus d'événements de surtension au cours de sa durée de vie, ce qui indique généralement que l'appareil est plus robuste et dure plus longtemps. Toutefois, une fois que l'indice kA est adapté à votre niveau d'exposition, un indice kA plus faible peut s'avérer utile. Indice de protection contre la tension (VPR) ou supérieur devient le facteur le plus critique pour la protection de l'électronique sensible.

6. Pourquoi les longueurs des câbles d'installation sont-elles si importantes ?

Inductance. Chaque centimètre de fil possède une inductance qui résiste à une variation rapide du courant (comme une surtension). Cette résistance crée une chute de tension le long du fil. Lors d'une surtension, cette tension s'ajoute à la tension de serrage du disjoncteur, augmentant ainsi la tension totale perçue par votre équipement. Les fils courts et droits minimisent cette tension supplémentaire.

7. Ai-je besoin de SPD dans une région où les orages sont peu fréquents ?

Oui. N'oubliez pas que jusqu'à 80% de surtensions sont générées en interne. Chaque fois qu'un moteur, un compresseur ou un variateur de vitesse effectue un cycle, il crée une petite surtension. Les commutations du réseau électrique se produisent également partout. Ces événements provoquent des dommages cumulatifs qui réduisent la durée de vie et la fiabilité de vos équipements électroniques.

8. Puis-je installer moi-même un SPD monté sur panneau ?

À moins d'être un électricien qualifié et agréé, vous ne devez pas le faire. L'installation implique de travailler à l'intérieur de panneaux électriques sous tension ou potentiellement sous tension, ce qui est extrêmement dangereux. Pour des raisons de sécurité, de conformité et d'efficacité, faites toujours appel à un professionnel.

Revenons à notre question initiale. La réponse n'est pas de mettre aveuglément un DOCUP sur tous mais pour installer un Le SPD est choisi stratégiquement à chaque point de transition critique de votre système électrique.

Cela signifie que :

En comprenant la différence entre les Type 1 vs Type 2 vs Type 3 SPD débat, en se penchant sur les comparaisons des matériaux En utilisant les technologies MOV, GDT et autres, et en mettant en œuvre une stratégie de protection contre les surtensions coordonnée et multicouche, conçue avec soin et installée avec précision, vous pouvez transformer une histoire de défaillance catastrophique en un non-événement. Les lumières peuvent vaciller, mais vos systèmes critiques resteront en ligne et vous pourrez dormir sur vos deux oreilles jusqu'à la prochaine tempête.