Dirección

304 North Cardinal

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Horas de trabajo

De lunes a viernes: de 7.00 a 19.00 horas

Fin de semana: 10.00 A 17.00 HORAS

Dirección

304 North Cardinal

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Horas de trabajo

De lunes a viernes: de 7.00 a 19.00 horas

Fin de semana: 10.00 A 17.00 HORAS

QUÉ ES MCCB: Son las 3 de la mañana. Suena el teléfono. La línea principal de producción de sus instalaciones está en silencio, los paneles de control están a oscuras y en el aire flota un ligero olor a plástico quemado. ¿El culpable? Un interruptor magnetotérmico de distribución principal que no se disparó durante una avería, provocando un fallo catastrófico del panel en lugar de un apagado controlado y aislado. En mis más de 15 años como ingeniero de campo, he visto esta situación exactamente más veces de las que puedo contar. Un dispositivo que cuesta unos pocos cientos de dólares, ignorado y que se supone que funciona, acaba causando cientos de miles en tiempo de inactividad y daños en los equipos.

Un disyuntor de caja moldeada (MCCB) no es sólo un interruptor; es la línea de defensa más importante entre sus costosos activos y el poder destructivo de los fallos eléctricos. Tratarlo como un componente que “cabe y se olvida” es una apuesta arriesgada. Pero entender qué es, cómo funciona y, lo que es más importante, cómo prueba MCCB se llevan a cabo los procedimientos, el juego cambia de juego a garantía.

Esta guía se basa en décadas de experiencia práctica. Iremos más allá de las definiciones de los libros de texto para ofrecerle un conocimiento práctico y profundo de los MCCB. Explicaremos qué son, las diferencias sutiles pero fundamentales entre los distintos tipos y proporcionaremos un marco exhaustivo paso a paso para probarlos. Al final de este artículo, dispondrá de los conocimientos necesarios para garantizar que sus interruptores sean activos para la protección, no pasivos a la espera de fallar.

En esencia, un disyuntor de caja moldeada es un dispositivo de protección eléctrica diseñado para proteger los circuitos de dos peligros principales: las sobrecargas y los cortocircuitos. Recibe su nombre de su carcasa, que es una “caja moldeada” resistente y no conductora, normalmente hecha de vidrio-poliéster o resina compuesta termoestable. .

Para entender su papel, piensa en una “Escalera de Protección”.”

La función principal de un MCCB es abrir automáticamente un circuito cuando detecta una corriente anormal, evitando daños y posibles incendios. A diferencia de un simple fusible, puede restablecerse (manual o automáticamente) una vez eliminado el fallo, con lo que se restablece la alimentación rápidamente.

Lo más importante: Un MCCB es un protector de circuitos de calidad industrial. Se distingue de un MCB residencial por sus valores nominales de corriente más altos, una capacidad de interrupción de fallos significativamente mayor y una construcción robusta diseñada para entornos comerciales e industriales exigentes.

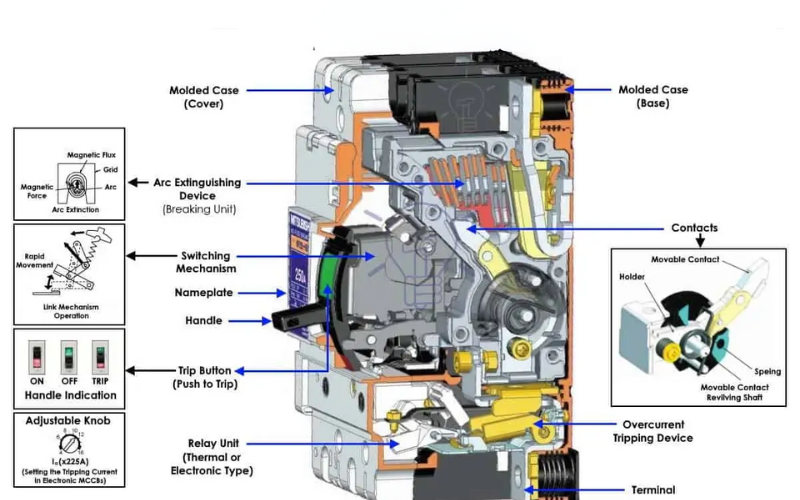

Para apreciar realmente un MCCB, hay que mirar dentro de la carcasa moldeada. Su funcionamiento es una sofisticada interacción de principios mecánicos y electromagnéticos, diseñados para reaccionar en milisegundos. Hay tres funciones básicas en juego: protección contra sobrecargas, protección contra cortocircuitos y extinción de arcos.

Imagen que muestra la compleja arquitectura interna de un MCCB estándar.

El mecanismo de accionamiento mecánico se encarga de separar rápidamente los contactos cuando se inicia un disparo.

Consejo profesional: La capacidad de corte (Icu o Ics) de un MCCB no es una sugerencia. Es la corriente de defecto máxima absoluta que el disyuntor está certificado para interrumpir sin explotar. Asegúrese siempre de que el valor nominal de su disyuntor supera la corriente de defecto disponible calculada en su ubicación, con un margen de seguridad 25% para futuros cambios en el sistema .

Un error común y peligroso es asumir que cualquier MCCB funcionará en cualquier circuito. La física de la interrupción de la corriente alterna (CA) y la corriente continua (CC) es fundamentalmente diferente, y utilizar el disyuntor equivocado puede tener consecuencias nefastas.

En un sistema de corriente alterna, la corriente pasa naturalmente por el cero 100 ó 120 veces por segundo (a 50/60 Hz). Este punto de “paso por cero” proporciona un momento natural de ayuda a la extinción del arco eléctrico. El arco pierde su energía y es más fácil de apagar.

En un sistema de CC, la corriente es constante. No hay paso por cero. Una vez formado el arco, se mantendrá mientras haya tensión suficiente, lo que dificulta enormemente su extinción. Esto requiere un enfoque de diseño completamente diferente.

He aquí un desglose de las principales diferencias:

| Característica | AC MCCB | DC MCCB |

|---|---|---|

| Método de extinción de arco | Se basa en el paso por cero de corriente y en una canaleta de arco estándar con placas metálicas. | Requiere extinción forzada del arco. Utiliza bobinas magnéticas de “soplado” para estirar el arco y conductos de arco multietapa más grandes y complejos. |

| Materiales de contacto | Aleaciones de plata-níquel o plata-grafito, optimizadas para la conductividad y el desgaste del arco estándar. | Aleaciones a base de plata con tungsteno u otros metales duros para soportar la mayor energía y la duración prolongada de un arco de CC. |

| Tensión nominal | Normalmente, hasta 690 V CA. Un disyuntor de 3 polos para 480 V CA sólo puede tener capacidad para 250 V CC. | Especificado para tensión continua, a menudo hasta 1500 V CC para aplicaciones como sistemas solares fotovoltaicos (FV). |

| Aplicaciones típicas | Distribución en edificios, control de motores industriales, sistemas de alimentación comercial. | Sistemas de energía solar, sistemas de almacenamiento de energía en baterías (BESS), transporte ferroviario, distribución de corriente continua en centros de datos. |

| Consideraciones sobre las pruebas | Probado según los parámetros de fallo de CA (factor de potencia). | Probado con una constante de tiempo específica (relación L/R, por ejemplo, T=4ms o 15ms) que simula la inductancia de un circuito de CC. |

Lo más importante: No utilice nunca un interruptor magnetotérmico de corriente alterna en una aplicación de corriente continua a menos que el fabricante lo indique explícitamente. El sistema de extinción de arcos de un disyuntor de CA estándar simplemente no está diseñado para manejar la energía continua de un arco de falta de CC y es probable que no funcione de forma segura.

Un MCCB puede permanecer inactivo durante años y luego ser llamado a funcionar en milisegundos. Confiar en que funcionará sin verificación es una negligencia. Un sólido programa de pruebas garantiza que siga siendo un protector fiable. Así que.., cómo prueba MCCB ¿Se realizan correctamente los procedimientos sobre el terreno? Seguimos un proceso estructurado de 6 pasos basado en las mejores prácticas del sector .

Antes de cualquier prueba eléctrica, empiece por los ojos y las manos. Este sencillo paso puede evitar fallos catastróficos.

Esta prueba verifica la integridad del aislamiento del MCCB, garantizando que no haya fugas de corriente entre polos o a tierra.

Esta prueba mide la resistencia de los contactos principales de conducción de corriente dentro del interruptor. Una resistencia alta indica que los contactos están picados, corroídos o desalineados, lo que provocará un sobrecalentamiento bajo carga.

Consejo profesional: Realice siempre la prueba de resistencia de contacto antes de la prueba de disparo por sobrecorriente. La prueba de disparo calienta los componentes internos, lo que distorsionará sus lecturas de resistencia de contacto. Si debe realizar la prueba después, deje que el interruptor se enfríe durante al menos 20 minutos.

Esta es la prueba más crítica. Garantiza que las funciones de disparo térmico y magnético funcionan de acuerdo con las especificaciones. Esta prueba requiere un equipo de prueba especializado de alta corriente.

Para los MCCB con unidades de disparo electrónicas, esta prueba verifica el estado de la electrónica de la unidad de disparo sin necesidad de inyectar una corriente elevada. Muchos equipos de prueba modernos pueden interactuar directamente con la unidad de disparo del interruptor para simular fallos y confirmar que la unidad envía una señal de disparo al mecanismo. Esta es una forma rápida y eficaz de probar el “cerebro” del interruptor.

Esta prueba es fundamental para garantizar la seguridad general del circuito, no sólo del propio disyuntor. Verifica que si se produce un fallo entre un conductor bajo tensión y la tierra, la corriente resultante será lo suficientemente alta como para disparar el MCCB en el tiempo requerido. Una impedancia de bucle alta puede impedir que el disyuntor se dispare, creando una situación peligrosa en la que los componentes metálicos pueden quedar bajo tensión sin que se despeje el fallo.

Las pruebas de campo no son arbitrarias; se rigen por sólidas normas industriales que garantizan la coherencia y la fiabilidad. Las dos normas más importantes para los MCCB son:

Incluso con un buen programa de pruebas, pueden surgir problemas. He aquí algunos problemas habituales y cómo abordarlos:

El disyuntor de caja moldeada es una extraordinaria pieza de ingeniería, diseñada para proteger nuestros sistemas eléctricos más críticos de la destrucción. Pero, como cualquier dispositivo de seguridad, su fiabilidad depende de su estado. Asumir que funcionará para siempre es una receta para tiempos de inactividad imprevistos y posibles desastres.

Comprendiendo cómo funciona un MCCB, respetando las diferencias entre las aplicaciones de CA y CC, e implementando un marco de pruebas sólido y basado en estándares, transformará ese interruptor de una responsabilidad potencial en un activo verificado y fiable. La respuesta a “cómo prueba MCCB” no se trata de un único procedimiento; se trata de un enfoque integral del mantenimiento que garantiza la protección cuando más se necesita. No espere a que le llamen a las 3 de la mañana para descubrir que sus defensas han fallado.

1. ¿Con qué frecuencia deben comprobarse los MCCB?

Para aplicaciones críticas como hospitales o centros de datos, las normas NETA/NEMA recomiendan realizar pruebas cada 1 a 3 años. Para aplicaciones industriales menos críticas, es habitual un intervalo de 3 a 5 años. La frecuencia debe ajustarse en función de la antigüedad del disyuntor, el entorno (por ejemplo, polvoriento o corrosivo) y la criticidad.

2. ¿Puedo utilizar un MCCB de CA para una aplicación solar de CC?

No, a menos que el fabricante le asigne explícitamente una tensión de CC y un poder de corte específicos. Un magnetotérmico de corriente alterna estándar probablemente no podrá extinguir con seguridad un arco de defecto de corriente continua. .

3. ¿Cuál es la diferencia entre las clasificaciones Icu e Ics?

4. Mi MCCB está caliente al tacto. ¿Es normal?

Un interruptor que soporta una parte significativa de su carga nominal se calentará debido a las pérdidas de I²R, lo cual es normal. Sin embargo, si se siente excesivamente caliente, o si el calor se concentra en los terminales, indica un problema como una conexión floja o una alta resistencia de contacto que necesita una investigación inmediata.

5. ¿Qué es un MCCB “limitador de corriente”?

Un MCCB limitador de corriente utiliza un diseño especial de contacto de alta repulsión que fuerza los contactos a separarse extremadamente rápido (en 1/4 de ciclo o menos) durante un fallo de alto nivel. Esto interrumpe la corriente antes de que pueda alcanzar su máximo potencial, lo que reduce significativamente la cantidad de energía destructiva que se transmite a los equipos aguas abajo. .

6. ¿Por qué se ha disparado mi disyuntor aguas abajo pero no el MCCB principal?

Esto es lo que idealmente debería ocurrir. Se llama coordinación selectiva. El sistema está diseñado para que el dispositivo de protección más cercano a la avería se abra primero, minimizando así el alcance del corte de energía. Si el disyuntor principal se dispara junto con el de aguas abajo, indica un fallo de coordinación .

7. ¿Puede repararse un MCCB de caja sellada?

No. Si un MCCB de caja sellada no supera alguna prueba eléctrica o tiene un mecanismo defectuoso, debe sustituirse. La apertura de una caja sellada invalida sus certificaciones de seguridad (como la lista UL) y hace que su uso no sea seguro. .

8. ¿Es siempre mejor una mayor capacidad de rotura?

Sí, desde el punto de vista de la seguridad, un mayor poder de corte proporciona un mayor margen de seguridad. Sin embargo, los disyuntores con capacidades extremadamente altas son más caros. El enfoque correcto es realizar un estudio de corriente de fallo para determinar la corriente de fallo disponible en la ubicación del disyuntor y seleccionar un disyuntor que supere con seguridad ese valor, equilibrando la seguridad y el coste.