Adresse

304 Nord Kardinal

St. Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Arbeitszeiten

Montag bis Freitag: 7AM - 7PM

Am Wochenende: 10AM - 5PM

Adresse

304 Nord Kardinal

St. Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Arbeitszeiten

Montag bis Freitag: 7AM - 7PM

Am Wochenende: 10AM - 5PM

WAS IST MCCB: Es ist 3 Uhr morgens. Das Telefon klingelt. Die Hauptproduktionslinie in Ihrem Werk ist totenstill, die Schalttafeln sind dunkel, und ein schwacher Geruch von verbranntem Plastik hängt in der Luft. Der Übeltäter? Ein MCCB in der Hauptverteilung, der während eines Fehlers nicht ausgelöst hat, so dass es zu einem katastrophalen Ausfall der Schalttafel statt zu einer kontrollierten, isolierten Abschaltung kam. Ich habe genau dieses Szenario in meinen mehr als 15 Jahren als Außendiensttechniker schon öfter erlebt. Ein Gerät, das ein paar hundert Dollar kostet, ignoriert wird und als funktionstüchtig gilt, verursacht am Ende Hunderttausende von Ausfallzeiten und Schäden an der Anlage.

Ein Molded Case Circuit Breaker (MCCB) ist nicht einfach nur ein Schalter; er ist die wichtigste Verteidigungslinie zwischen Ihren teuren Anlagen und der zerstörerischen Kraft elektrischer Fehler. Ihn als eine Komponente zu behandeln, die man einfach einbauen und vergessen kann, ist ein Glücksspiel. Aber wenn man versteht, was er ist, wie er funktioniert, und vor allem, wie MCCB-Test Verfahren durchgeführt werden, wird das Spiel vom Glücksspiel zur Sicherheit.

Dieser Leitfaden basiert auf jahrzehntelanger Praxiserfahrung. Wir gehen über die Definitionen aus dem Lehrbuch hinaus, um Ihnen ein praktisches, tiefgehendes Verständnis von MCCBs zu vermitteln. Wir erläutern, was sie sind, die subtilen, aber entscheidenden Unterschiede zwischen den Typen und bieten einen umfassenden, schrittweisen Rahmen für ihre Prüfung. Am Ende dieses Artikels werden Sie über das Wissen verfügen, das Sie benötigen, um sicherzustellen, dass Ihre Unterbrecher Schutzgüter sind und keine Verbindlichkeiten, die auf einen Ausfall warten.

Im Kern ist ein Molded Case Circuit Breaker ein elektrisches Schutzgerät, das dazu dient, Stromkreise vor zwei Hauptgefahren zu schützen: Überlastungen und Kurzschlüsse. Seinen Namen hat er von seinem Gehäuse, das ein robustes, nicht leitendes “Formgehäuse” ist, das in der Regel aus Glas-Polyester oder duroplastischem Verbundharz besteht. .

Um seine Rolle zu verstehen, denken Sie an eine “Schutzleiter”.”

Die Hauptaufgabe eines MCCB besteht darin, einen Stromkreis automatisch zu öffnen, wenn er einen abnormalen Strom feststellt, um Schäden und mögliche Brände zu verhindern. Im Gegensatz zu einer einfachen Sicherung kann er (manuell oder automatisch) zurückgesetzt werden, nachdem der Fehler behoben wurde, so dass die Stromversorgung schnell wiederhergestellt werden kann.

Das Wichtigste zum Mitnehmen: Ein MCCB ist ein Stromkreisschutzschalter für die Industrie. Er unterscheidet sich von einem MCB für den Hausgebrauch durch seine höheren Nennströme, eine deutlich höhere Fehlerunterbrechungskapazität und eine robuste Konstruktion, die für anspruchsvolle gewerbliche und industrielle Umgebungen ausgelegt ist.

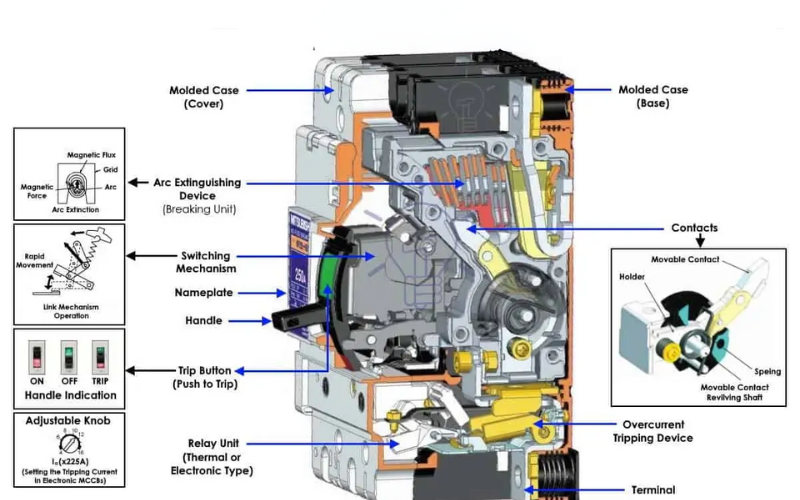

Um einen MCCB richtig einschätzen zu können, muss man einen Blick in sein Gehäuse werfen. Seine Funktionsweise ist ein ausgeklügeltes Zusammenspiel mechanischer und elektromagnetischer Prinzipien, die so konzipiert sind, dass sie innerhalb von Millisekunden reagieren. Es gibt drei Kernfunktionen: Überlastschutz, Kurzschlussschutz und Lichtbogenlöschung.

Das Bild zeigt die komplexe interne Architektur eines Standard-MCB.

Der mechanische Betätigungsmechanismus ist für die schnelle Trennung der Kontakte bei Auslösung verantwortlich.

Profi-Tipp: Das auf einem MCCB angegebene Ausschaltvermögen (Icu oder Ics) ist kein Vorschlag. Es handelt sich um den absoluten maximalen Fehlerstrom, den der Schalter ohne Explosion unterbrechen kann. Stellen Sie immer sicher, dass die Bemessung Ihres Schalters den berechneten verfügbaren Fehlerstrom an seinem Standort übersteigt, mit einer 25% Sicherheitsspanne für zukünftige Systemänderungen. .

Ein häufiger und gefährlicher Fehler ist die Annahme, dass jeder MCCB für jeden Stromkreis geeignet ist. Die Physik der Unterbrechung von Wechselstrom (AC) und Gleichstrom (DC) unterscheidet sich grundlegend, und die Verwendung des falschen Schalters kann schlimme Folgen haben.

In einem Wechselstromsystem durchläuft der Strom natürlich 100 oder 120 Mal pro Sekunde den Nullpunkt (bei 50/60 Hz). Dieser “Nulldurchgang” ist ein natürlicher Moment der Unterstützung beim Löschen des Lichtbogens. Der Lichtbogen verliert seine Energie und ist leichter zu löschen.

In einem Gleichstromsystem ist der Strom konstant. Es gibt keinen Nulldurchgang. Wenn sich ein Lichtbogen einmal gebildet hat, bleibt er so lange bestehen, wie die Spannung ausreicht, was das Löschen erheblich erschwert und einen völlig anderen Konstruktionsansatz erfordert.

Hier eine Übersicht über die wichtigsten Unterschiede:

| Merkmal | AC MCCB | DC-MCCB |

|---|---|---|

| Lichtbogen-Extinktionsverfahren | Verlassen sich auf einen Stromnulldurchgang und einen Standard-Lichtbogenschacht mit Metallplatten. | Erfordert eine erzwungene Lichtbogenlöschung. Verwendet magnetische “Ausblas”-Spulen zum Strecken des Lichtbogens und größere, komplexere mehrstufige Lichtbogenschächte. |

| Kontakt Materialien | Silber-Nickel- oder Silber-Graphit-Legierungen, optimiert für Leitfähigkeit und normalen Lichtbogenverschleiß. | Legierungen auf Silberbasis mit Wolfram oder anderen Hartmetallen, um der höheren Energie und längeren Dauer eines Gleichstromlichtbogens standzuhalten. |

| Spannungswerte | Normalerweise für bis zu 690V AC ausgelegt. Ein 3-poliger Unterbrecher, der für 480 V AC ausgelegt ist, ist möglicherweise nur für 250 V DC ausgelegt. | Spezifiziert für Gleichspannung, oft bis zu 1500V DC für Anwendungen wie Solar-Photovoltaik-Systeme (PV). |

| Typische Anwendungen | Gebäudeverteilung, industrielle Motorsteuerung, kommerzielle Stromversorgungssysteme. | Solarenergiesysteme, Batteriespeichersysteme (BESS), Schienenverkehr, Gleichstromverteilung in Rechenzentren. |

| Überlegungen zur Prüfung | Geprüft nach den AC-Fehlerparametern (Leistungsfaktor). | Getestet mit einer bestimmten Zeitkonstante (L/R-Verhältnis, z. B. T=4ms oder 15ms), die die Induktivität eines Gleichstromkreises simuliert. |

Das Wichtigste zum Mitnehmen: Verwenden Sie niemals einen Wechselstrom-Schutzschalter in einer Gleichstromanwendung, es sei denn, er ist vom Hersteller ausdrücklich mit einer Gleichstrom-Bewertung gekennzeichnet. Das Lichtbogenlöschsystem in einem Standard-AC-Schalter ist einfach nicht für die kontinuierliche Energie eines DC-Fehlerlichtbogens ausgelegt und wird wahrscheinlich nicht sicher funktionieren.

Ein MCCB kann jahrelang inaktiv sein und dann innerhalb von Millisekunden zum Einsatz gebracht werden. Darauf zu vertrauen, dass er ohne Überprüfung funktioniert, ist fahrlässig. Ein solides Prüfprogramm stellt sicher, dass er ein zuverlässiger Schutz bleibt. So, wie MCCB-Test Verfahren vor Ort korrekt durchgeführt werden? Wir folgen einem strukturierten, 6-stufigen Prozess, der auf den besten Praktiken der Branche basiert. .

Beginnen Sie vor jeder elektrischen Prüfung mit Ihren Augen und Händen. Dieser einfache Schritt kann katastrophale Ausfälle verhindern.

Mit diesem Test wird die Unversehrtheit der Isolierung des MCCB überprüft, um sicherzustellen, dass kein Strom zwischen den Polen oder in den Boden entweicht.

Bei dieser Prüfung wird der Widerstand der stromführenden Hauptkontakte im Inneren des Unterbrechers gemessen. Ein hoher Widerstand deutet auf löchrige, korrodierte oder falsch ausgerichtete Kontakte hin, die unter Last zu Überhitzung führen.

Profi-Tipp: Führen Sie immer den Kontaktwiderstandstest durch vor den Überstromauslösetest. Der Auslösetest erwärmt die internen Komponenten, was zu einer Verfälschung der Kontaktwiderstandsmessungen führt. Wenn Sie den Test danach durchführen müssen, lassen Sie den Schalter mindestens 20 Minuten lang abkühlen.

Dies ist der kritischste Test. Sie stellt sicher, dass die thermischen und magnetischen Auslösefunktionen gemäß den Spezifikationen funktionieren. Für diese Prüfung ist ein spezielles Hochstromprüfgerät erforderlich.

Bei MCCBs mit elektronischen Auslösern wird bei dieser Prüfung der Zustand der Elektronik des Auslösers überprüft, ohne dass ein hoher Strom eingespeist werden muss. Viele moderne Prüfgeräte können direkt mit der Auslöseeinheit des Schalters verbunden werden, um Fehler zu simulieren und zu bestätigen, dass die Einheit ein Auslösesignal an den Mechanismus sendet. Dies ist eine schnelle und effektive Methode, um das “Gehirn” des Schalters zu testen.

Diese Prüfung ist entscheidend für die Sicherheit des gesamten Stromkreises, nicht nur des Schalters selbst. Sie stellt sicher, dass bei einem Fehler zwischen einem stromführenden Leiter und der Erde der resultierende Strom hoch genug ist, um den MCCB innerhalb der erforderlichen Zeit auszulösen. Eine hohe Schleifenimpedanz kann die Auslösung des Schalters verhindern und eine gefährliche Situation schaffen, in der metallische Komponenten unter Spannung stehen können, ohne dass der Fehler behoben wird.

Feldtests sind nicht willkürlich, sondern orientieren sich an robusten Industrienormen, die Konsistenz und Zuverlässigkeit gewährleisten. Die beiden wichtigsten Normen für MCCBs sind:

Selbst bei einem guten Prüfprogramm können Probleme auftreten. Hier sind einige häufige Probleme und wie man sie angehen kann:

Der Molded Case Circuit Breaker ist ein bemerkenswertes Stück Technik, das unsere wichtigsten elektrischen Systeme vor Zerstörung schützen soll. Aber wie jede Sicherheitseinrichtung ist er nur so zuverlässig wie sein Zustand. Die Annahme, dass er ewig funktionieren wird, ist ein Rezept für ungeplante Ausfallzeiten und mögliche Katastrophen.

Wenn Sie verstehen, wie ein MCCB funktioniert, die Unterschiede zwischen Wechsel- und Gleichstromanwendungen berücksichtigen und einen robusten, auf Standards basierenden Testrahmen implementieren, verwandeln Sie den Schalter von einer potenziellen Belastung in eine verifizierte, zuverlässige Anlage. Die Antwort auf “wie MCCB-Test”Es geht nicht nur um ein einzelnes Verfahren, sondern um ein umfassendes Wartungskonzept, das Schutz garantiert, wenn er am dringendsten benötigt wird. Warten Sie nicht auf den Anruf um 3 Uhr morgens, um herauszufinden, dass Ihre Schutzmaßnahmen versagt haben.

1. Wie oft sollten MCCBs geprüft werden?

Für kritische Anwendungen wie Krankenhäuser oder Rechenzentren empfehlen die NETA/NEMA-Normen eine Prüfung alle 1 bis 3 Jahre. Für weniger kritische industrielle Anwendungen ist ein Intervall von 3 bis 5 Jahren üblich. Die Häufigkeit sollte je nach Alter des Schalters, Umgebung (z. B. staubig oder korrosiv) und Kritikalität angepasst werden.

2. Kann ich einen AC-MCCB für eine DC-Solaranwendung verwenden?

Nein, es sei denn, er ist vom Hersteller ausdrücklich für eine bestimmte Gleichspannung und ein bestimmtes Schaltvermögen ausgelegt. Ein Standard-Wechselstrom-Schutzschalter wird einen Gleichstrom-Fehlerlichtbogen wahrscheinlich nicht sicher löschen können. .

3. Was ist der Unterschied zwischen Icu- und Ics-Einstufungen?

4. Mein MCCB fühlt sich warm an. Ist das normal?

Ein Schalter, der einen erheblichen Teil seiner Nennlast trägt, fühlt sich aufgrund von I²R-Verlusten warm an, was normal ist. Fühlt er sich jedoch übermäßig heiß an oder konzentriert sich die Wärme auf die Klemmen, deutet dies auf ein Problem wie einen Wackelkontakt oder einen hohen Kontaktwiderstand hin, das sofort untersucht werden muss.

5. Was ist ein “strombegrenzender” MCCB?

Ein strombegrenzender MCCB verwendet ein spezielles Kontaktdesign mit hohem Rückstoß, das die Kontakte bei einem Fehler mit hohem Pegel extrem schnell auseinander drückt (in einem 1/4-Zyklus oder weniger). Dadurch wird der Strom unterbrochen, bevor er seinen vollen potenziellen Spitzenwert erreichen kann, was die Menge an zerstörerischer Energie, die an nachgeschaltete Geräte weitergegeben wird, erheblich reduziert. .

6. Warum hat mein nachgeschalteter Unterbrecher ausgelöst, aber nicht der Haupt-MCCB?

Im Idealfall sollte dies geschehen. Es heißt gezielte Koordinierung. Das System ist so ausgelegt, dass die Schutzeinrichtung, die dem Fehler am nächsten liegt, zuerst auslöst, um das Ausmaß des Stromausfalls zu minimieren. Wenn der Hauptschalter zusammen mit dem nachgeschalteten Schutzschalter auslöst, deutet dies auf einen Koordinationsfehler hin. .

7. Kann ein MCCB mit versiegeltem Gehäuse repariert werden?

Nein. Wenn ein MCCB mit versiegeltem Gehäuse einen elektrischen Test nicht besteht oder einen fehlerhaften Mechanismus aufweist, muss er ersetzt werden. Durch das Öffnen eines versiegelten Gehäuses werden die Sicherheitszertifikate (z. B. die UL-Listung) ungültig und die Verwendung wird unsicher. .

8. Ist eine höhere Bruchlast immer besser?

Ja, unter dem Gesichtspunkt der Sicherheit bietet ein höheres Ausschaltvermögen eine größere Sicherheitsmarge. Allerdings sind Leistungsschalter mit extrem hoher Leistung teurer. Der richtige Ansatz besteht darin, eine Fehlerstromstudie durchzuführen, um den verfügbaren Fehlerstrom am Standort des Schalters zu ermitteln und einen Schalter auszuwählen, der diesen Wert sicher überschreitet, wobei Sicherheit und Kosten abzuwägen sind.