Adresse

304 Nord Kardinal

St. Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Arbeitszeiten

Montag bis Freitag: 7AM - 7PM

Am Wochenende: 10AM - 5PM

Adresse

304 Nord Kardinal

St. Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Arbeitszeiten

Montag bis Freitag: 7AM - 7PM

Am Wochenende: 10AM - 5PM

Es ist 2 Uhr morgens an einem Dienstag. Ihr Telefon summt auf dem Nachttisch, und die Anrufer-ID ist der Leiter der Nachtschicht in der Fabrik. Ihr Herz sinkt. Das sind nie gute Nachrichten. Vor einer Stunde ist ein Gewitter über die Gegend gezogen, aber es war meilenweit entfernt - kein direkter Einschlag, nicht einmal ein Flackern der Lichter in Ihrem Haus. Aber die Stimme des Supervisors ist verzweifelt. “Leitung 3 ist ausgefallen. Die Haupt-SPS, zwei VFDs und die Hälfte der E/A-Karten sind durchgebrannt. Wir sind völlig aufgeschmissen.”

Ich bin seit über 15 Jahren leitender Anwendungstechniker und kann Ihnen gar nicht sagen, wie oft ich eine Variation dieser Geschichte gehört habe. Der Übeltäter ist nicht der Sturm selbst, sondern der unsichtbare Killer, den er durch die Stromleitungen schickt: eine transiente Überspannung oder das, was wir gemeinhin als Stromstoß bezeichnen. Dabei handelt es sich um eine energiereiche, kurzzeitige Stromspitze, die empfindliche elektronische Geräte innerhalb einer Mikrosekunde lahm legen oder zerstören kann. Die Kosten belaufen sich nicht nur auf ein paar Tausend Dollar für eine neue SPS, sondern auf Zehn- oder Hunderttausende in Form von Produktionsausfällen, verpassten Terminen und Notreparaturkosten.

Die meisten Einrichtungen glauben, dass sie durch ein äußeres Blitzableitersystem geschützt sind. Aber das schützt die Gebäudestruktur nur vor einem direkten, feuerauslösenden Einschlag. Die massiven Stromstöße, die in Ihre Strom-, Daten- und Kommunikationsleitungen geleitet und induziert werden, werden dadurch nicht aufgehalten.

Hier kommen Überspannungsschutzgeräte (SPDs) ins Spiel. Aber die Frage, die ich am häufigsten höre, lautet: “Welche brauche ich? Und wo? Sollte ich SPDs an jeder Schalttafel anbringen?” Die Antwort ist nicht nur “ja” oder “nein”. Die richtige Antwort ist eine strategische, die auf dem Verständnis der verschiedenen Arten von SPDs und der darin enthaltenen Technologien beruht. Dieser Leitfaden führt Sie durch das Warum, Was und Wo des Überspannungsschutzes, vom Netzeingang bis hin zu den empfindlichsten Geräten in Ihrer Etage. Materialvergleich zwischen Typ 1, Typ 2 und Typ 3 SPD.

Bevor wir uns mit den verschiedenen Typen befassen, sollten wir klären, was ein SPD eigentlich tut. Stellen Sie sich Ihr elektrisches System wie ein Rohrleitungssystem mit einem konstanten, normalen Wasserdruck (Spannung) vor. Ein Spannungsstoß ist wie ein plötzlicher, massiver Wasserschlag - eine Druckspitze, die Rohre zum Bersten bringen und Geräte beschädigen kann.

Eine SPD wirkt wie ein Druckablassventil. Unter normalen Spannungsbedingungen sitzt es da, tut nichts und stellt eine hohe Impedanz dar. Wenn es jedoch eine Spannungsspitze über einem bestimmten Schwellenwert (seiner Klemmspannung) feststellt, schafft es sofort einen Pfad mit sehr niedriger Impedanz, um die überschüssige Energie sicher zur Erde abzuleiten. Sobald die Spannung wieder normal ist, schließt sich das “Ventil” wieder. Das alles geschieht innerhalb von Nanosekunden.

Überspannungen haben zwei Hauptursachen:

Da diese Bedrohungen sowohl von außen als auch von innen kommen, ist ein einzelner Überspannungsschutz nicht ausreichend. Die effektivste Strategie ist ein koordinierter, mehrschichtiger Ansatz, der als “Verteidigung in der Tiefe” bekannt ist. Stellen Sie sich das wie ein Wasserfiltersystem vor: Ein grobes Sieb am Einlass fängt die großen Steine auf, ein feinerer Filter stromabwärts fängt die Sedimente auf, und ein letzter Kohlefilter am Wasserhahn sorgt dafür, dass das Wasser rein ist. SPDs funktionieren nach demselben Prinzip. SPDs: Nicht nur einmalig und fertig

Ein mehrstufiges oder kaskadiertes Überspannungsschutzsystem.

Die Industrie, die sich an Normen wie UL 1449 und der IEC 62305-Reihe orientiert, hat SPDs in “Typen” eingeteilt, je nachdem, wo sie installiert werden und für welche Art von Überspannung sie ausgelegt sind. Dies zu verstehen Typ 1 vs. Typ 2 vs. Typ 3 SPD Hierarchie ist die Grundlage für einen soliden Schutzplan.

Ein SPD vom Typ 1 ist die erste Verteidigungslinie Ihres Systems. Es handelt sich um einen hochleistungsfähigen Pförtner, der am Netzeingang installiert wird, genau dort, wo der Strom vom Versorgungsunternehmen in Ihr Gebäude gelangt. Er kann entweder auf der “Leitungsseite” (vor dem Hauptschalter) oder auf der “Lastseite” (nach dem Hauptschalter) installiert werden, aber seine Hauptaufgabe ist es, die stärksten externen Überspannungen zu bewältigen.

Ein SPD des Typs 2 ist der gebräuchlichste Typ, der Ihre Unterverteiler und Verteilerschalttafeln in einer Anlage schützt. Er ist für die Installation auf der “Lastseite” eines Überstromschutzgeräts (wie eines Leistungsschalters) vorgesehen.

Ein SPD des Typs 3 ist die letzte Schutzschicht und befindet sich direkt neben dem zu schützenden Gerät. Diese Geräte finden Sie in überspannungsgeschützten Steckdosenleisten, Steckdosenadaptern oder manchmal auch direkt in empfindlicher Elektronik eingebaut.

| Merkmal | Typ 1 SPD | Typ 2 SPD | Typ 3 SPD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Einbauort | Service-Eingang (Netz- oder Lastseite) | Verteilungs-/Verzweigungspaneele (Lastseite) | Point-of-Use / Wandsteckdose |

| Primäres Ziel | Externe Überspannungen mit hoher Energie (Blitzschlag) | Restliche externe und interne Überspannungen | Schwache Rest- und lokale Überspannungen |

| Test Wellenform | 10/350 µs (Iimp) | 8/20 µs (Ein) | 8/20 µs (In) & Kombinationswelle |

| Überspannungsschutz | Sehr hoch (z. B. 25-100 kA Iimp) | Mittel bis hoch (z. B. 20-60 kA In) | Niedrig (z. B. 3-10 kA In) |

| Wichtigste Technologie | Funkenspalt, Gasentladungsrohr (GDT) | Metall-Oxid-Varistor (MOV) | MOV, TVS-Diode |

| Fokus Schutz | Abzweigung massiver Energie | Abfangen häufiger Stromstöße | Niedrigste Klemmspannung (VPR/Up) |

Was steckt eigentlich in diesen Geräten, das sie zu diesen elektrotechnischen Hochgeschwindigkeitsleistungen befähigt? Der SPD-“Typ” definiert seine Anwendung, aber die Technologie der Komponenten im Inneren ist das, was die eigentliche Arbeit leistet. Die Wahl des Materials entscheidet über die Leistung, die Lebensdauer und die Kosten des Geräts. Es gibt vier Hauptkomponenten, die oft in hybriden Kombinationen verwendet werden.

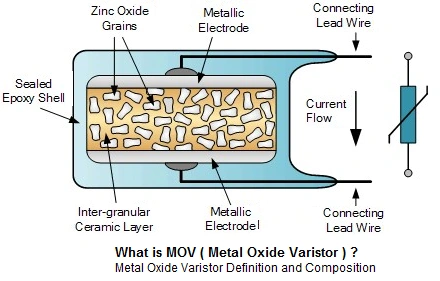

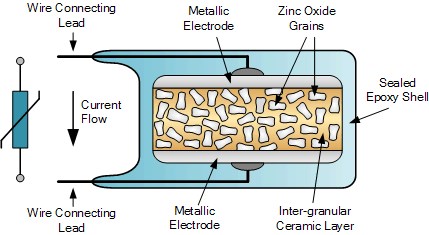

Das MOV ist das unbestrittene Arbeitspferd des Überspannungsschutzes und findet sich in der überwiegenden Mehrheit der SPDs vom Typ 2 und 3. Es handelt sich um ein keramisches Halbleiterbauelement (hauptsächlich Zinkoxid mit anderen Metalloxiden), das wie ein spannungsempfindlicher Schalter funktioniert. Bei normalen Spannungen erzeugen die Korngrenzen einen hohen Widerstand. Wenn die Spannung in die Höhe schießt, brechen diese Grenzen innerhalb von Nanosekunden zusammen, und der Widerstand sinkt auf nahezu Null, so dass der Stoßstrom zur Erde abgeleitet wird.

Ein GDT ist ein einfaches, aber leistungsfähiges Gerät, das aus zwei oder mehr Elektroden besteht, die in einer kleinen Keramikröhre eingeschlossen sind, die mit einem Inertgas gefüllt ist. Wenn die Spannung an den Elektroden die Durchbruchspannung des Gases übersteigt, bildet sich ein Lichtbogen, der einen extrem niederohmigen Pfad (einen virtuellen Kurzschluss) erzeugt.

Eine Funkenstrecke ist der ursprüngliche Überspannungsschutz mit “roher Gewalt”. In ihrer einfachsten Form besteht sie aus zwei Leitern, die durch einen kleinen Luftspalt getrennt sind. Wenn eine sehr hohe Spannung auftritt (z. B. durch einen Blitz), überspringt ein Lichtbogen die Lücke und leitet den Strom ab. Moderne “getriggerte Funkenstrecken” sind fortschrittlichere Versionen, die eine dritte Elektrode oder einen elektronischen Schaltkreis verwenden, um zuverlässiger und bei niedrigeren, besser kontrollierten Spannungen zu zünden.

TVS-Dioden sind Halbleiterbauelemente, ähnlich wie superschnelle Zenerdioden, die speziell für den Überspannungsschutz entwickelt wurden. Sie sind die Präzisionsinstrumente der SPD-Welt und klemmen die Spannung mit chirurgischer Genauigkeit.

| Technologie | Reaktionszeit | Stoßstrom-Kapazität | Lebensdauer / Degradation | Präzision beim Klemmen | Relative Kosten | Primäre Anwendung |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOV | Schnell (~25 ns) | Mittel bis Hoch | Verschlechtert sich mit jedem Stromstoß | Gut | $$ | Typ 2, Typ 3, Hybrid T1 |

| GDT | Mittel (~100 ns) | Sehr hoch | Lang; robust | Messe | $$$ | Typ 1, Daten-/Telekom-Leitungen |

| Funkenspalt | Langsam (>100 ns) | Extrem hoch | Sehr lang | Schlecht | $$$$ | Typ 1 (Schwerlast) |

| TVS-Diode | Sehr schnell (<1 ns) | Niedrig | Lang (wenn nicht überbeansprucht) | Ausgezeichnet | $ | Typ 3, Schutz auf Vorstandsebene |

Das Wichtigste zum Mitnehmen: Beim perfekten SPD geht es oft nicht um eine einzelne Technologie, sondern um ein hybride Ausführung die die Stärken der einzelnen Komponenten nutzt. Eine gängige und hocheffektive Kombination in einem Hochleistungs-SPD vom Typ 1 oder Typ 2 ist ein GDT oder Spark Gap für massive Energieaufnahme, gepaart mit einem MOV zur Verwaltung der Ansprechzeit und der Klemmspannung, um sowohl einen brachialen Schutz als auch eine schnelle, präzise Klemmung zu gewährleisten.

Und nun zum wichtigsten Teil: Wie wenden Sie all dies auf Ihre Einrichtung an? Ein guter Entwurf folgt einem klaren, logischen Prozess.

Die Norm IEC 62305 führt das Konzept der Blitzschutzzonen (LPZ) ein. Stellen Sie sich Ihr Gebäude als eine Reihe verschachtelter Kästen vor, wobei jede Schicht mehr Schutz bietet. Ihr Ziel ist es, ein SPD an der Grenze jedes Zonenübergangs zu installieren, um die Überspannungsenergie schrittweise zu reduzieren.

Das Konzept der Blitzschutzzone (LPZ), das die Platzierung von SPD an den Zonengrenzen zeigt.

Nutzen Sie diesen einfachen Baum als Orientierungshilfe für Ihren Auswahlprozess.

Ich habe schon mehrere tausend Dollar teure SPD-Systeme gesehen, die durch schlampigen Einbau unbrauchbar wurden. Die Physik ist unerbittlich. Halten Sie sich strikt an diese Regeln.

1. Kann ich einfach ein SPD des Typs 3 (wie eine Steckdosenleiste) installieren und die größeren Geräte weglassen?

Nein. Dies ist ein häufiger und kostspieliger Fehler. Ein Gerät des Typs 3 ist nur für kleine, verbleibende Überspannungen ausgelegt. Eine große Überspannung aus dem Stromnetz oder ein Blitzeinschlag in der Nähe zerstört das Gerät und wahrscheinlich auch die daran angeschlossenen Geräte. Es benötigt die vorgeschalteten Geräte des Typs 1 und 2, um die Überspannung auf ein erträgliches Maß zu reduzieren.

2. Woher weiß ich, ob mein Überspannungsschutz ersetzt werden muss?

Die meisten modernen SPDs für den Schalttafeleinbau (Typ 1 und 2) verfügen über eine Statusanzeige oder eine mechanische Markierung. Grün bedeutet in der Regel, dass das Gerät funktioniert; rot, aus oder eine andere Farbe bedeutet, dass der Schutz beeinträchtigt ist und das Gerät ausgetauscht werden muss. Einige moderne Systeme verfügen auch über Fernüberwachungskontakte, die mit Ihrem Gebäudemanagementsystem verbunden werden können.

3. Was ist der Unterschied zwischen einem Überspannungsschutz und einem Stromkreisunterbrecher?

Ein Stromkreisunterbrecher schützt vor Überstrom-ein Zustand, in dem das System über einen längeren Zeitraum zu viel Strom zieht (z. B. ein Kurzschluss oder ein überlasteter Motor). Es handelt sich um eine langsam wirkende thermisch-magnetische Vorrichtung. Ein SPD schützt vor Überspannung-eine extrem schnelle, kurzzeitige Spannungsspitze. Sie dienen zwei völlig unterschiedlichen, aber gleichermaßen wichtigen Schutzfunktionen.

4. Schützt ein Überspannungsschutz meine Geräte vor einem direkten Blitzeinschlag?

Kein Gerät kann 100% Schutz vor einem direkten Einschlag in die Struktur selbst bieten. Ein ordnungsgemäß installiertes Blitzschutzsystem (LPS) ist für den direkten Einschlag zuständig. Ein SPD des Typs 1 ist dafür ausgelegt, den immensen Strom zu bewältigen, der die auf die Stromleitungen von den Streik. Sie sind zwei Teile eines vollständigen Systems.

5. Ist ein höherer kA-Wert immer besser?

Bis zu einem gewissen Punkt. Ein höherer kA-Wert (für Iimp oder In) bedeutet, dass das Gerät mehr Überspannungsenergie oder mehr Überspannungsereignisse während seiner Lebensdauer verkraften kann, was im Allgemeinen auf ein robusteres und langlebigeres Gerät hindeutet. Sobald Sie jedoch einen angemessenen kA-Wert für Ihr Expositionsniveau haben, ist ein niedrigerer Spannungsschutzklasse (VPR) oder höher wird zum entscheidenden Faktor für den Schutz empfindlicher Elektronik.

6. Warum ist die Länge der Installationskabel so wichtig?

Induktivität. Jeder Zentimeter Draht hat eine Induktivität, die einer schnellen Stromänderung (wie einem Stromstoß) widersteht. Dieser Widerstand erzeugt einen Spannungsabfall entlang des Kabels. Bei einem Spannungsstoß addiert sich diese Spannung zu der Klemmspannung des SPD und erhöht die Gesamtspannung, die an Ihren Geräten anliegt. Kurze, gerade Drähte minimieren diese zusätzliche Spannung.

7. Brauche ich SPDs in einem Gebiet mit seltenen Gewittern?

Ja. Denken Sie daran, dass intern Überspannungen von bis zu 80% erzeugt werden. Jedes Mal, wenn ein Motor, ein Kompressor oder ein VFD in Betrieb geht, wird ein kleiner Stromstoß erzeugt. Auch die Umschaltung des Versorgungsnetzes findet überall statt. Diese Ereignisse verursachen kumulative Schäden, die die Lebensdauer und Zuverlässigkeit Ihrer elektronischen Anlagen verringern.

8. Kann ich ein SPD für den Schaltschrankeinbau selbst installieren?

Wenn Sie kein qualifizierter und zugelassener Elektriker sind, sollten Sie das nicht tun. Bei der Installation wird in stromführenden oder potenziell stromführenden Schalttafeln gearbeitet, was extrem gefährlich ist. Beauftragen Sie aus Gründen der Sicherheit, der Einhaltung von Vorschriften und der Effizienz immer einen Fachmann.

Kehren wir zu unserer ursprünglichen Frage zurück. Die Antwort lautet nicht, blindlings ein EPPD anzulegen jede Paneel, sondern die Installation eines strategisch ausgewählte SPD an jedem kritischen Übergangspunkt in Ihrem elektrischen System.

Dies bedeutet:

Durch das Verständnis des Unterschieds in der Typ 1 vs. Typ 2 vs. Typ 3 SPD Debatte, die sich mit dem Materialvergleiche von MOV-, GDT- und anderen Technologien und die Implementierung einer koordinierten, mehrschichtigen Überspannungsschutzstrategie - die sorgfältig geplant und präzise installiert wird - können Sie einen katastrophalen Ausfall in ein Nicht-Ereignis verwandeln. Die Lichter könnten flackern, aber Ihre kritischen Systeme bleiben online, und Sie können den nächsten Sturm ruhig durchschlafen.